The Reserve Bank started raising its official cash rate in October last year and following the 0.5% rise on May 25 the rate now sits at 2.0%. This is the level at which many of us economists think the Reserve Bank is neither stimulating the economy nor restricting it. That is, 2% is considered to be the neutral cash rate. From here we move into restrictive territory.

Rising rates are restraining the economy

But are current fixed mortgage rates at neutral levels? Does the best two year rate on offer at around 5.2% feel like it is not restricting the economy, housing market, and inflationary pressures? What about the five year rate around 5.8%? Not really.

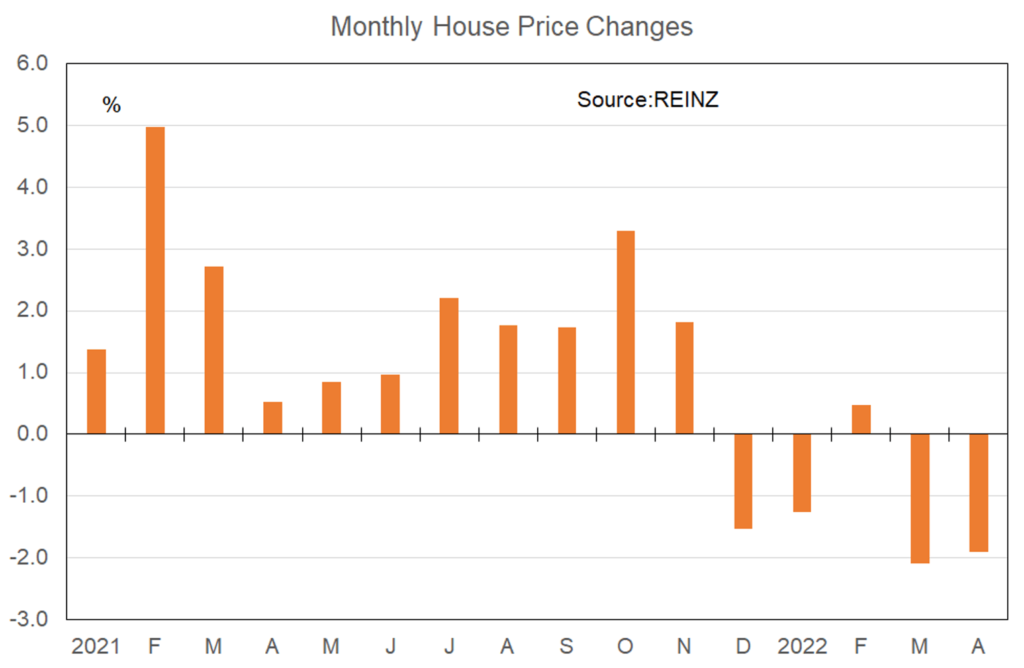

We have plenty of evidence in hand that the levels to which fixed mortgage rates have risen are already restricting the economy. It is not just that house prices are already falling at a firm pace (actually about half of the pace of rises over 2020-21). We can see the impact from my monthly Spending Plans Survey.

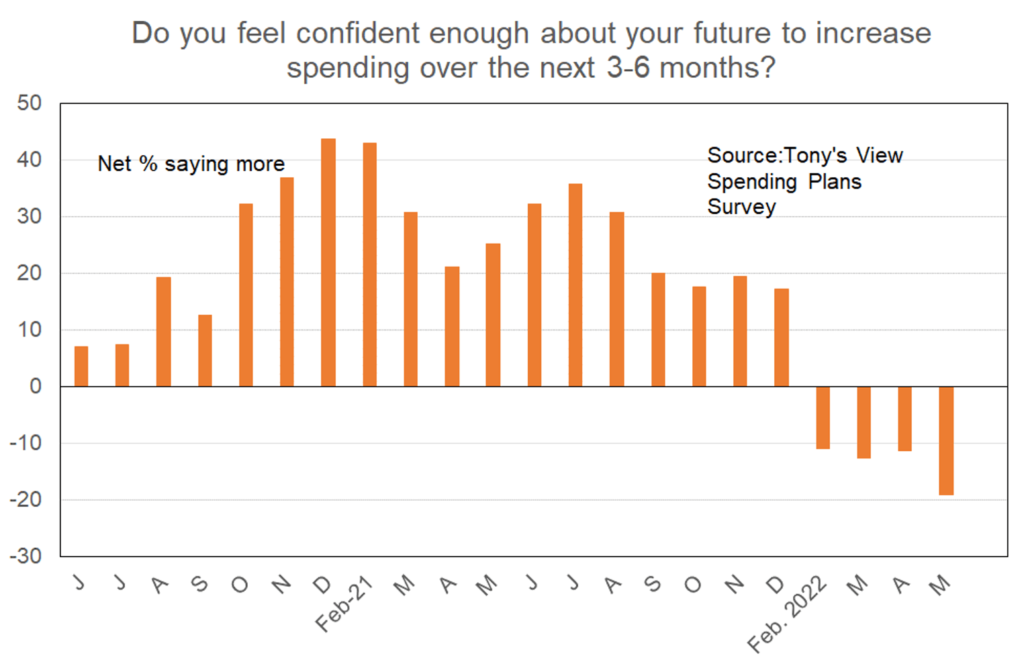

Consumer spending

In this survey I ask people whether they plan spending more or less on things generally over the next 3-6 months. On average over 2020-21 a net 25% of respondents said that they will spend more. That fell to a net 11% in February saying they would spend less, and the latest reading is a net 20% negative. Consumer spending is already being crunched.

Technically we have to say that it is not just higher mortgage costs causing people to rein in their spending plans. There is also the soaring cost of living (inflation) and the ending of a two-year binge on home renovations and buying things like spas. So, more than monetary policy is in play.

Is a recession on the way?

But from the central bank’s point of view, it does not matter exactly what is causing the crunch to consumer spending and the increasing number of forecasters discussing the potential for recession. A weakening NZ economy is what the Reserve Bank wants to see if inflation is to be eventually brought back down. That means there is little need for them to issue any particularly strong warnings about having to throw the economy into recession as they did in 2008 in order to suppress inflation.

However, a key characteristic of our economy nowadays is that we are short of key resources such as labour. That explains why even through the world growth outlook is worsening, the Reserve Bank has lifted its projected peak for the cash rate from 3.4% to 3.9% with the peak to come mid-2023 rather than mid-2024. They are seeking to accelerate restraint in the economy so that resource availability better matches demand conditions.

My pick for the peak in the official cash rate takes into account the weakness already appearing and sits at 3.5% rather than the Reserve Bank’s 3.9%.

What does this mean for mortgage rates?

There is probably another 1-1.5%% to be added eventually to the one year fixed mortgage rate and maybe 0.5% – 1.0% to rates for two years and longer. But the high rate rise expectations in the financial markets do explain one characteristic of this tightening cycle.

Consider the last time a true tightening cycle got underway at the start of 2005. It took two and a half years for house prices to start falling and just over that time for household spending to be well reined in. That is because no-one believed interest rates would rise all that much – the Reserve Bank repeatedly said as much along the way.

House price changes

This time mortgage rates have risen very quickly early in the cycle, house prices are already falling, householders already reining in spending, and business and consumer sentiment levels are fairly poor.

What does this imply for borrowers?

As discussed in my last column two months ago we will eventually reach a position where markets pull back from anticipating more and more rate rises from the Reserve Bank and instead focus on when rates will fall. When that happens long term fixed mortgage rates will fall below short term rates and people will have to be careful not to fall into the trap of taking a long rate simply because it will be relatively cheap.

Interest rates move in cycles and my pick in this still hugely uncertain environment we are all operating in is that they will start falling over 2024-25. Therefore, it makes sense that despite all the high inflation worries which abound at the moment there is a decided shift by borrowers away from fixing three years towards fixing two years and increasingly one year.

That makes sense even though none of us can have high certainty regarding how long short rates remain at their cyclical peaks. The challenge for borrowers recently and currently has been rolling onto higher fixed rates and budgeting for larger cash outflows every fortnight. The challenge eventually will shift to how long one can stay fixing one year waiting for all rates to fall when longer rates are lower.