Up until the very early 1990s, if you were borrowing money to buy a house the only option was a floating mortgage rate. For a while in the 1960s into the 1970s a small number of people could access some low fixed rates. But for most of us the 1990s brought a new world where greater thought needed to be given to how to manage interest rate risk.

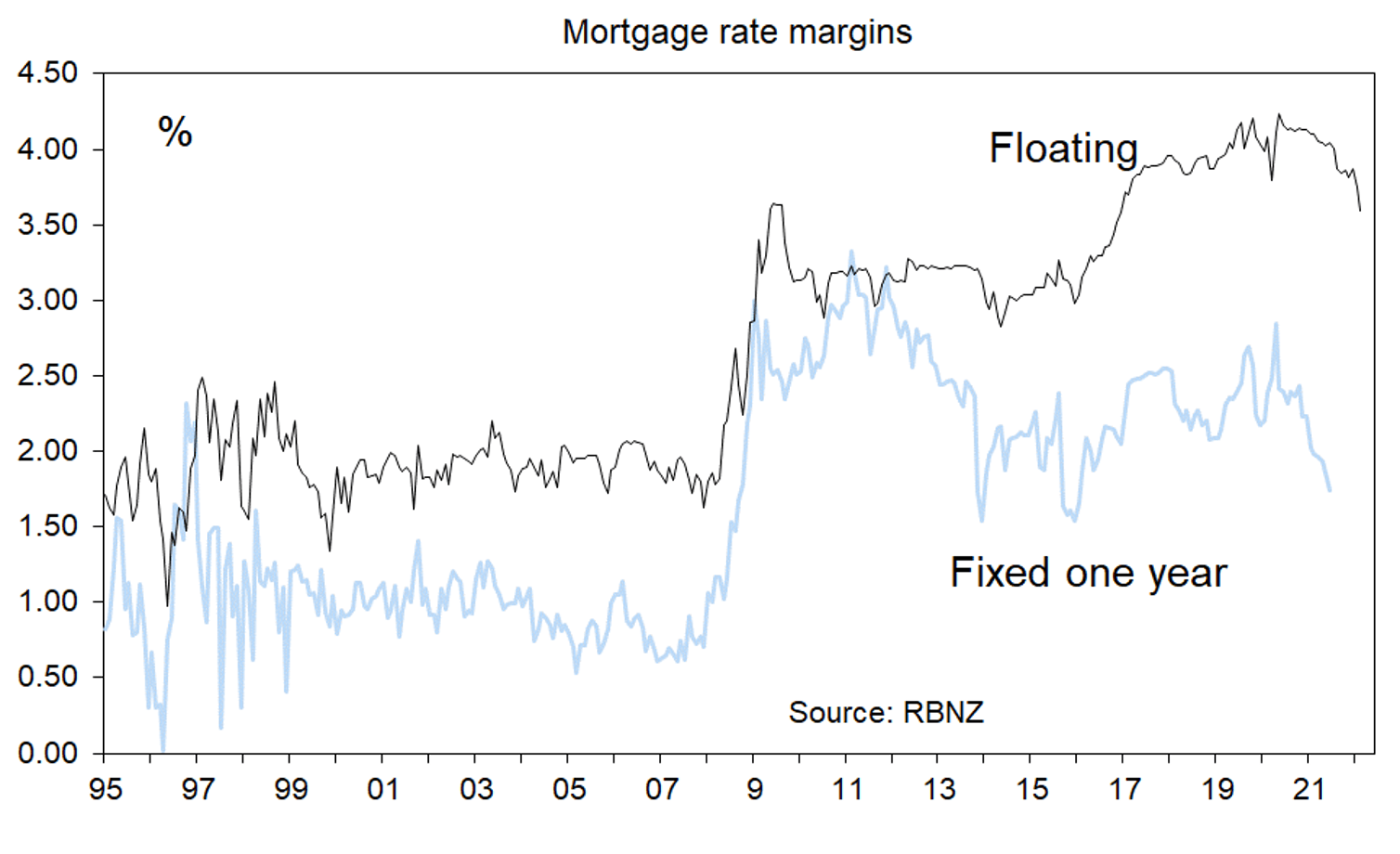

Initially banks offered just a one-year fixed rate. But in the following few years longer term rates out to five years appeared. A few years later a seven year fixed rate hit the market for home buyers. When the fixed rates first appeared banks in New Zealand used them to compete for new customers. This led to the locking in of much lower margins for banks on their fixed rate than their floating rate lending.

In Australia banks chose to compete by discounting their floating rates for periods of six to 12 months. This meant that fairly quickly Kiwis opted to fix their rates to a far greater degree than Australian home buyers. But history shows that we have not chosen to fix for long time periods. In fact, just two years ago the last lender left offering a seven year fixed rate withdrew the product from the market because hardly anyone wanted to fix for seven years.

We focus on the now

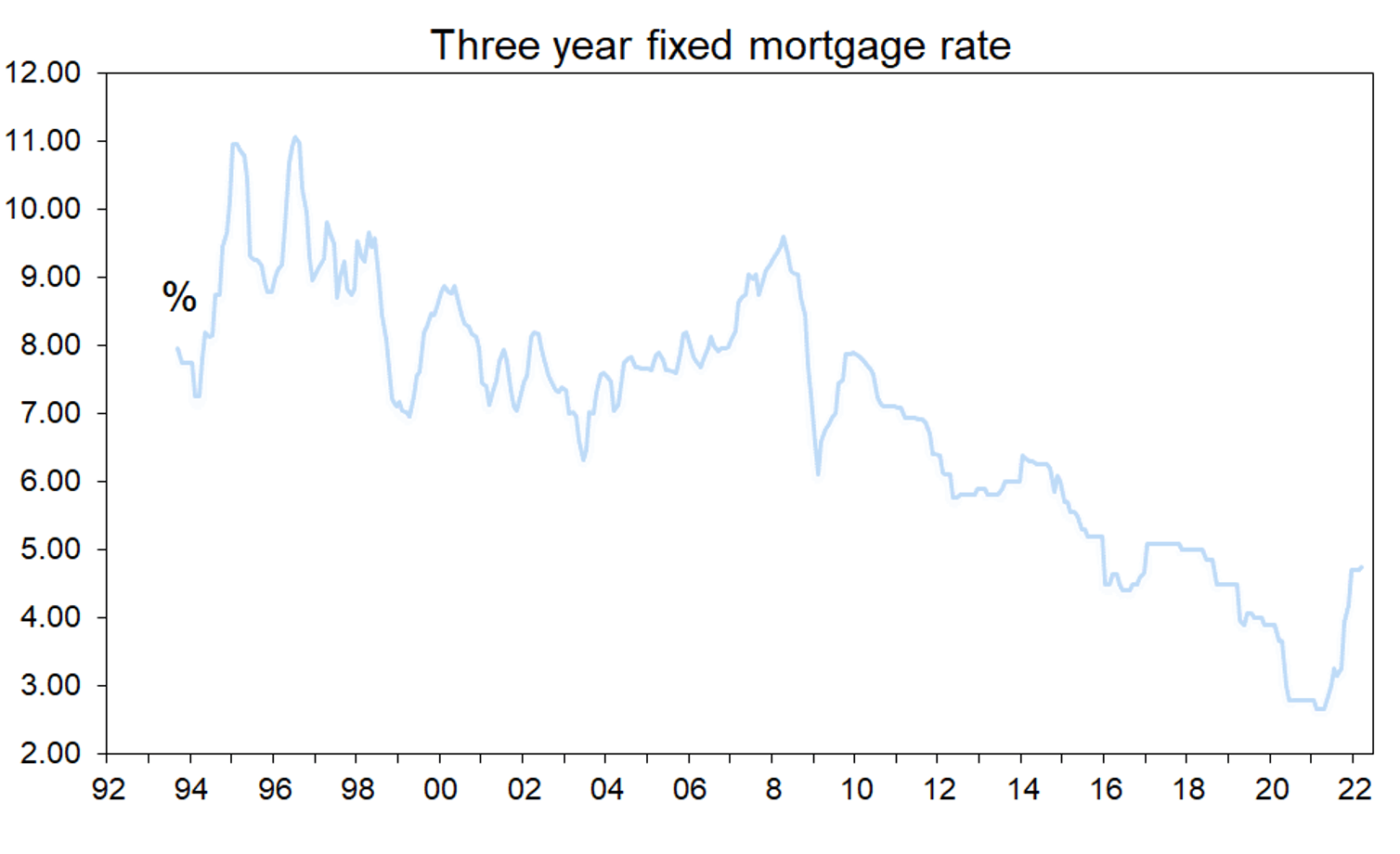

It’s actually worse than that. Experience across a number of interest rate cycles since 1992 has shown that we Kiwis only rarely fix our interest rate for longer than three years. Why? Partly it is because we seem to have shorter planning time horisons than the likes of Americans who usually fix their rate for 30 years.

Partly it will be because we have seen a lot of volatility in our interest rates over the past three decades and sometimes those who fixed in for long periods found themselves paying high rates some 2% or more above what the people who fixed only for 1-3 years were paying. But this is a problem of perception we have created for ourselves.

When we don’t, the timing is bad

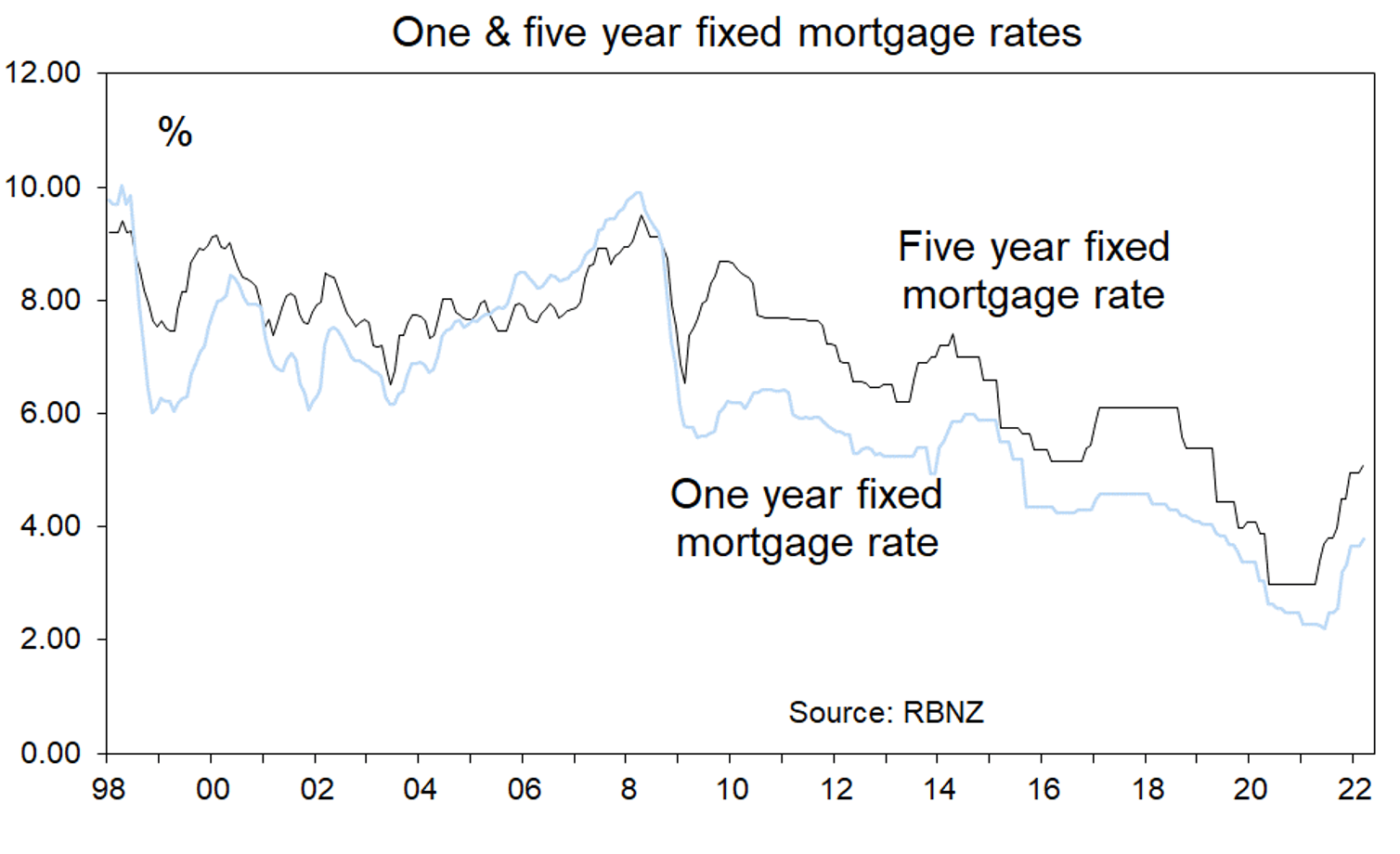

Back in those two years the five year fixed rate was lower than shorter term rates. Many people fixed five years. But within less than a year all interest rates fell sharply and when people went to the bank to try and break their now high five year fixed rate in order to get a lower rate they learnt all about break cost.

When a bank in New Zealand lends fixed it also borrows fixed and locks in a margin. Banks cannot break five year deposits from customers if you want to break your five year fixed mortgage rate.

Thus, over the years many borrowers have experienced or know the stories of people who fixed long at the wrong point in the interest rates/economic cycle and got caught out.

At the moment the interest rates for the likes of the 1-3 year periods are still below the four and five year fixed rates. Almost everyone is locking in for two or three years, and that is probably what I would do as well if I were currently a fresh borrower.

History repeats itself

But probably within 12 months we will once again see the short rates above long rates. Try to remember this article for when that happens and this final comment regarding why this warning is important. When fixed rates for short terms rise above those for long terms it is a signal that much weaker growth in the economy lies ahead and interest rates will soon fall. In fact, just as the markets in the United States anticipate the rapid rise in interest rates this year will partially reverse come 2024, so too is this likely to happen in New Zealand over 2024-25.

Interest rates move in cycles, but that is a topic for perhaps the next article.