Mortgage rates up - again.

Maybe we’ll be right this time. That is probably the best way us analysts could start our reports regarding interest rates at the moment because our optimism these past few months regarding interest rates for home buyers peaking has been unfortunately misplaced.

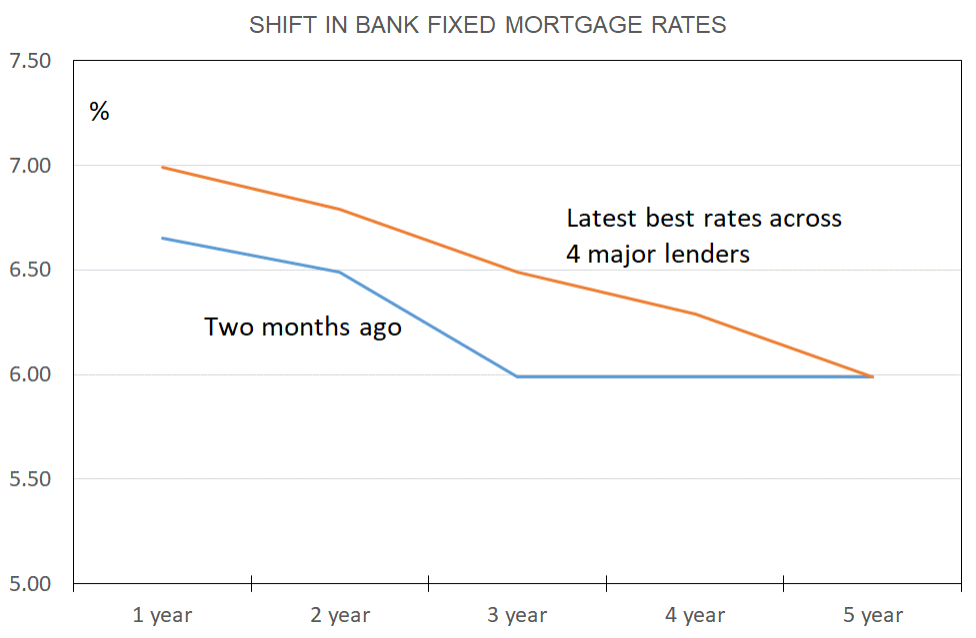

When I last wrote this column towards the end of May the commonly available one year fixed mortgage rate was sitting near 6.65% and the two year rate near 6.49%. Now, both rates are about 0.3% higher. These increases have occurred over a period when the Reserve Bank’s official cash rate has been unchanged at 5.5% and the RB have signalled they do not believe they will need to raise the rate again this cycle.

So, why the boost to mortgage rates? The easy answer is that bank funding costs for these short terms have risen about 0.2% – 0.3%. But why have these costs gone up at a time when almost all the measures of inflation expectations, capacity availability, and business pricing plans have been improving? The economy has even been confirmed as entering a technical recession late last year.

There was a strong degree of optimism early this year

It all comes down to developments in the United States. There was a strong degree of optimism early this year that inflation was being brought comfortably under control by the Federal Reserve’s rate rises and much further tightening would not be required. Unfortunately, there has been less weakness in consumer spending than hoped and indicators for the labour market have surprised on the strong side.

A similar thing has been seen in Australia and in both instances this has led to extra rises in wholesale interest rates in those economies. This has fed through into some upward pressure on borrowing costs here.

What this means is something important. To take a pick on when fixed mortgage rates start falling in New Zealand and how quickly they go down you need to have a view not just on the NZ economy but that of the United States in particular and Australia to a lesser degree.

Unfortunately, we are in a post-pandemic environment which is not something any of us or any of the models put together by deep research economists have experience of. This is all new to us and because we all failed to pick the extent to which the pandemic stimulus would boost inflation it would not be reasonable to expect that we can accurately pick when inflation will fall close to 2% here, let alone in two other economies.

Value in splitting one’s interest rate exposure across terms

This is valuable information for people looking to manage their interest rate exposure over the next few years. Fixing one year would generally be considered the optimal thing to do at this point in the monetary policy cycle when no further tightening is likely. But if you can’t place high reliance on forecasts then you need to give greater thought to the risk that inflation does not fall quickly and monetary policy is not eased here for some considerable time. This means there is value in splitting one’s interest rate exposure across terms.

Perhaps a 50:50 split between one and two year fixed rates would be optimal. Maybe even one-third each to one, two and three years.

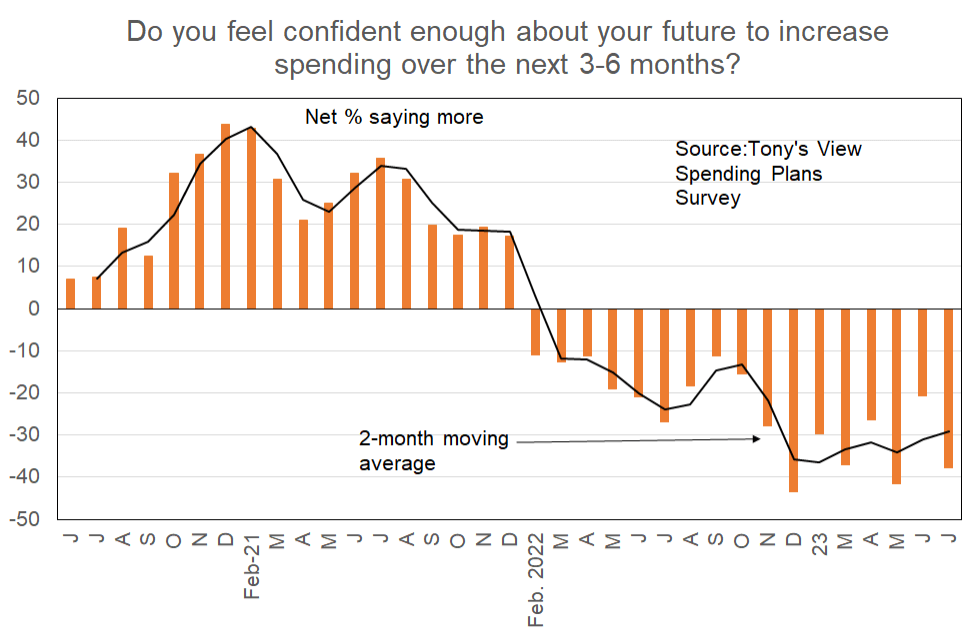

Still, everyone likes a view and the one I am running with is this. There has been a slight deterioration in the outlook for our economy recently because of new worries about the degree of strength in China’s economy this year and next. Some export commodity prices have weakened, and my monthly Spending Plans Survey has identified a fresh deterioration in consumer plans for spending over the coming 3-6 months.

June quarter inflation rate came in marginally higher than expected

These things argue in favour of monetary policy being eased well ahead of the Reserve Bank’s indication of about October next year. However, the June quarter inflation rate came in marginally higher than expected on some underlying measures, and there has been some weakness in the NZ dollar which will partly feed through into some higher import costs.

For the moment my view is that the first easing of the official cash rate will come just before the middle of 2024. That implies that we will see some slight reductions in fixed mortgage rates before the end of this year, but probably not before the election. This is especially the case as banks appear to be making some efforts to regrow their mortgage margins just as demand for credit appears to be rising in association with the housing market turning upward.

As regards the speed with which monetary policy is eased through 2024 and 2025, that is anyone’s guess in all honesty. We need a lot more information on the response of inflation to rate rises so far before we can start to make decent picks about the speed of rate declines.