The altered outlook

But from almost two months ago things started to go wrong. Some inflation numbers – most notably in the United States – came in higher than expected. Data on the state of labour markets and plans by businesses to hire people remained strong rather than edging off. And central bankers became concerned that the level of inflation optimism was simply excessive.

They especially became worried about markets pricing in monetary policies easing from late in 2023 and how this was pushing down medium to long-term fixed borrowing costs. So, things have changed.

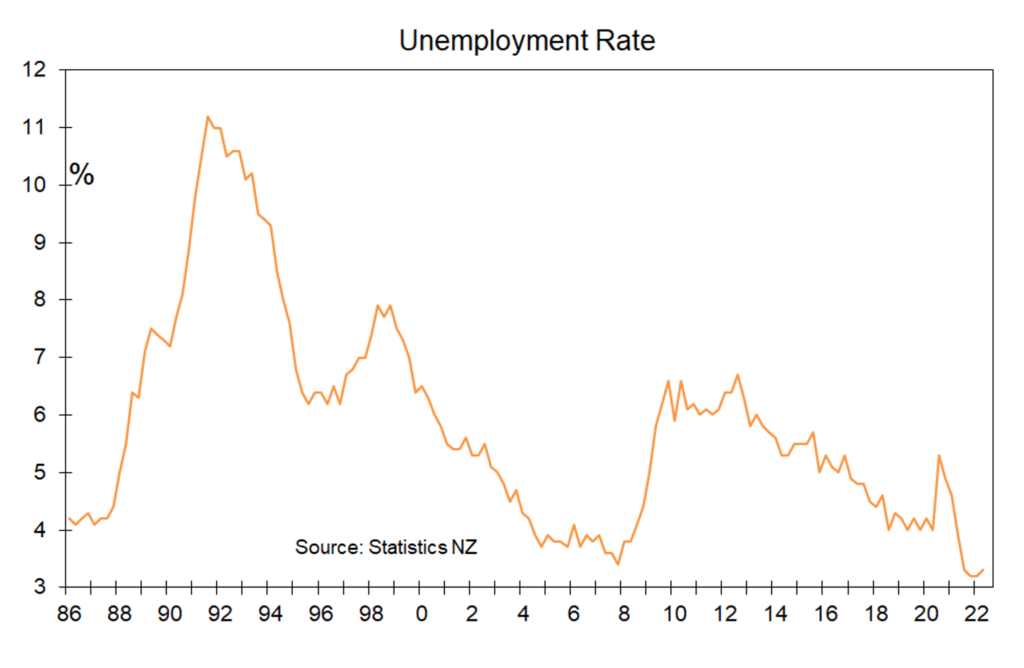

Central banks have not only accelerated the pace with which they are raising interest rates, they are also projecting higher peaks for their cash rates, falls not happening until much later than earlier indicated, and using strong words of warning. Specifically, they are openly talking about the potential need to throw their economies into recession in order to get unemployment rates up and solidly suppress inflation.

A high degree of uncertainty

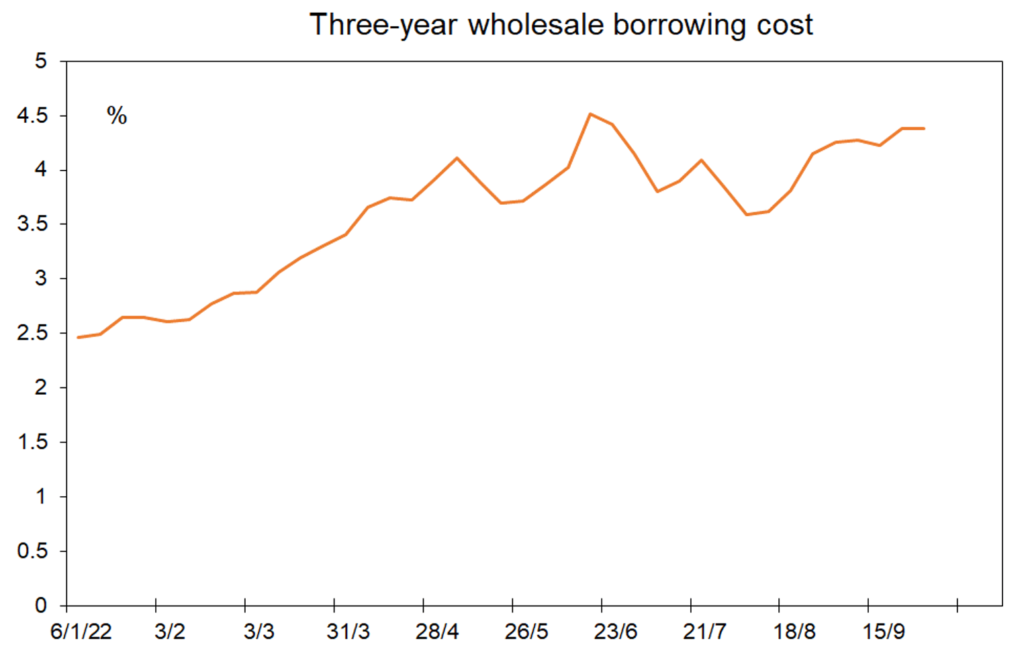

There is a high degree of uncertainty now surrounding where monetary policies are going and that has led to some hefty increase in wholesale borrowing costs around the world. The benchmark United States ten year government bond yield has gone up to near 3.7% from 2.7% early in August and an earlier peak of 3.4% in June.

Locally, the three year cost to banks in New Zealand of borrowing money to lend to you and I at a fixed rate for three years has risen to near 4.55% from 3.6% at the start of August and an earlier peak of 4.5% in June. The one year wholesale interest rate banks pay has risen to near 4.5% from 3.8% early in August and the earlier peak in June of 4.15%.

As a result of these new rises in borrowing costs banks are taking away the cuts to fixed lending rates for the short to medium terms which they made early in August just before things started turning sour. Bad timing – but then we were all gripped by optimism about inflation back then.

The global focus now is on whether the United States will have to be pushed into a recession by the Federal Reserve in order to get inflation back to 2%. If so, they will join the UK and European Union who are probably already in recession because of the energy crisis induced by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Recession remains very unlikely

Here in New Zealand recession remains very unlikely. We are receiving help from the low NZ dollar, good export prices, good fiscal accounts, backlog of construction work, returning tourists, students, and migrants, and high job security.

However, we will need to see some decent degree of loosening in the labour market in the near future before we can be reasonably certain that inflation will comfortably head back to near 2% in 2024. That is why it looks likely that the borrowing costs facing NZ homeowners and fresh buyers will remain elevated through to the end of 2023.

By then it is likely that optimism about inflation falling will have returned and we could see some sizeable declines in fixed rates for periods of two years and beyond. That is why when all is said and done, the implication for borrowers from the altered inflation outlook is not that much different from what it was back in August.

For most people fixing one year will be optimal. But it would pay to recognise the huge uncertain factors in play by considering fixing some portion of one’s debt also for two years – or even longer for those of highly conservative bent.

Tony Alexander is an independent economist with additional commentary available at www.tonyalexander.nz